- Research

Published: | By: Ute Schönfelder

Industrial wastewater, slurry, microplastics and heavy metals—the list of pollutants that end up in bodies of water is long. Waters that are intensively used by humans, such as rivers, lakes and coasts, are contaminated to varying degrees and with a wide variety of substances. In order to avert dangers to humans and the environment, the EU has set itself the goal of restoring all bodies of water in the EU member states to their natural state by 2030.

"This requires us to know the natural state first," says Associate Professor Dr Peter Frenzel from the University of Jena. "And we also need methods that provide reliable information on water quality," continues the researcher from the Institute of Geosciences. While various biological and chemical methods have already been established for the latter, reconstructing the pre-industrial, natural state of a body of water is difficult.

Archive of the pre-industrial state of waters

Peter Frenzel's team is working on this issue and has now presented a critical overview of methods that can be used to answer both questions in a recent publication. As the researchers write in the journal "Earth-Science Reviews", tiny ostracods are suitable bioindicators for current water quality and can also be used as an archive of the pre-industrial state of waters, providing information about the original state of the body of water.

"Ostracods react sensitively to environmental changes such as salinity, temperature and pollution. This makes them very suitable for monitoring lakes and rivers," says Dr Olga Schmitz, the lead author of the study now presented. "Based on their species diversity and abundance, we can not only reconstruct current and past environmental conditions, but even predict future changes. This can be particularly important for agriculture and water management with regard to climate change."

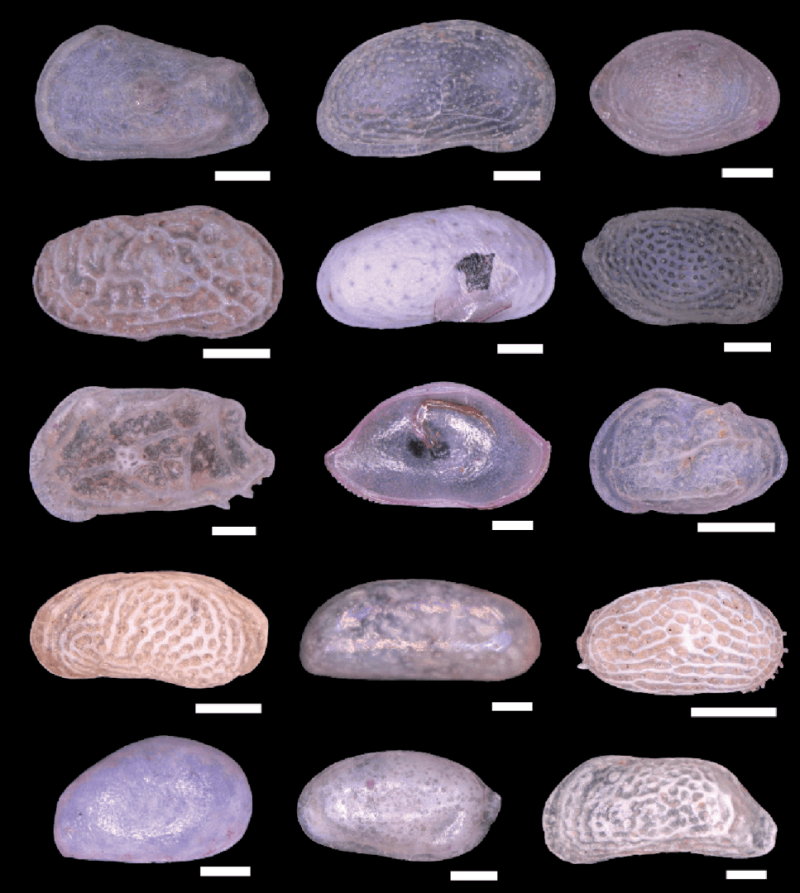

Olga Schmitz focussed on ostracods as part of her doctorate. This publication is the first comprehensive compilation of the current state of research and knowledge on the role of ostracods as bioindicators. The animals, which are only up to one millimetre in size, can be found in almost all bodies of water: in lakes, rivers, lagoons and even in groundwater and hot springs. Around 15,000 species living today are known, and around 20,000 fossilized specimens have been described. The microscopically small crustaceans are encased in calcareous shells that remain in the mud and sand at the bottom of the water for a long time after their death. These can be used by researchers in their environmental analyses and as fossils for the reconstruction of environmental and climatic conditions.

AI helps to identify and analyse microorganisms

However, the geoscientist is not only evaluating existing studies on ostracods. She and the Jena team have also sampled a wide variety of waters themselves and analysed the ostracod populations, from the Great Stechlin Lake in Brandenburg to coastal waters in South Africa. In collaboration with researchers from the University of Hong Kong, they are now even developing the use of artificial intelligence to identify, count and measure the ostracods in the samples under the microscope.

"For our analyses, we only need one cubic centimetre of sediment to draw conclusions about anthropogenic influences or past hydrological changes, which makes this method particularly cost-effective," says Olga Schmitz, underlining another advantage of the method. The researchers hope that their recently published overview could lead to the targeted use of ostracods for environmental management and the renaturalization of waters in Germany and beyond in the future.

Calcareous shells of various ostracods from the Umlalazi estuary in South Africa. The scale bar length corresponds to 100 micrometres respectively.

Picture: Olga SchmitzOriginal publication:

Olga Schmitz et al. Ostracoda (Crustacea) as indicators of anthropogenic impacts — A review. Earth-Science Reviews 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2025.105049External link